Avec les films TRIXI (1969), THE SUN AND THE MOON (2007) de Stephen Dwoskin et un livre d’entretien de 112 pages bilingue (fr/en) avec Stephen Dwoskin (2009).

English below

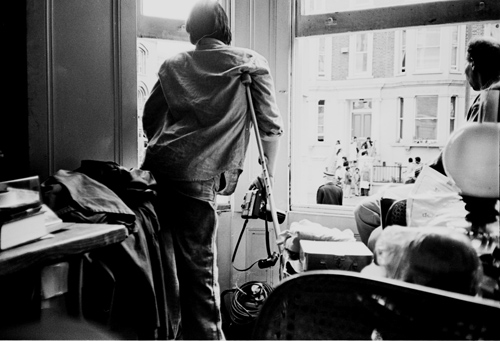

Brixton, quartier Afro au sud de Londres. Un peu à l’écart, Beechdale Road avec ses maisons mitoyennes et petits jardins attenants. Ici se trouve la maison monde habitée par Stephen Dwoskin, le champ d’expérimentation de son cinéma. Maison monde car au fil des années, Stephen, atteint par la poliomyélite à l’âge de neuf ans, s’est enraciné là, entre ses objets, ses tableaux, l’arbre dans le jardin, sa table de montage au premier étage et ses pièces qui servent de studio de tournage.

En mai 2009, nous sommes allés lui rendre visite. Nous voulions discuter avec lui de son cinéma, dont nous avions récemment fait l’expérience marquante (Moment, Trixi, Behindert, Girl, Central Bazaar, Oblivion, The Sun and the Moon). Dwoskin propose au spectateur de partager l’intensité du regard – le sien, et la vision de ses films avait travaillé en nous des questions liées au désir et à la sexualité, à la douleur, au rapport du corps et du politique. Que faisons-nous de nos libertés ? Qu’est-ce que l’incarnation ? Qu’est-ce que l’amour ? Pendant trois jours, nous avons exploré avec lui, et parfois quelques amis, une partie de sa vie et de son oeuvre.

Cette publication rend compte de ces conversations et s’agence d’une part à certains de ses travaux graphiques et des photos personnelles, et d’autre part à l’édition inédite des films Trixi et The Sun and the Moon.

Trixi et The Sun and the Moon sont deux œuvres créées à presque 40 ans d’écart, avec la même « performeuse », Beatrice Cordua, et avec des outils différents, le pellicule et la vidéo.

———————————-

Brixton tube station, at the heart of London’s busy African neighbourhood. Down the road and round the corner, to Beechdale Road. In this quiet terraced side street Stephen Dwoskin’s house-and-world is to be found, the scene of his cinematographic experiments. A house-and-world for, with the passing of time, Stephen, who contracted polio at the age of nine, has become rooted here, amidst his objects, his paintings, the tree in his garden, his editing table upstairs and the rooms which are his film studios.

We came to visit him in 2009. We wanted to talk to him about his films, which we had recently experienced (Moment, Trixi, Behindert, Girl, Central Bazaar, Oblivion, The Sun and the Moon), and in which he gives his spectators the opportunity to share the intensity of his gaze. Seeing his films had prompted a whole series of questions for us: on sexuality, on pain, on the relationship between the body and politics; on the use we make of our freedom; on the meaning of embodiment; and on love.

We spent three days in his company, and on occasion that of some friends, exploring a part of his life and his work.

This publication gives an account of our conversations. It also includes graphic illustrations by and photographs of Dwoskin himself, as well as the hitherto unpublished films Trixi and The Sun and the Moon.

Almost 40 years separate the making of Trixi from that of The Sun and the Moon. Both works, using different technologies, feature the same performer, Beatrice Cordua. The first was made on film and the second on video.

Revue papier

Le livre sera composé de 112 pages couleur et noir & blanc.

Au cours de l’entretien, nous avons visité avec Stephen Dwoskin l’atelier de son cinéma, à la recherche de ses inspirations. Le cinéaste nous a parlé de politique et de souffrance, de liberté et de contrainte, d’amour. Il nous a parlé du passage entre l’espace physique et un espace mental, entre la matière numérique et un espace métaphorique.

Nous avons choisi de publier cet entretien dans les deux langues : l’adaptation française et le texte anglais, langue maternelle du cinéaste et dans laquelle nous avons conduit l’entretien.

Dvd

TRIXI (1969, 30 minutes, 16mm/couleur)

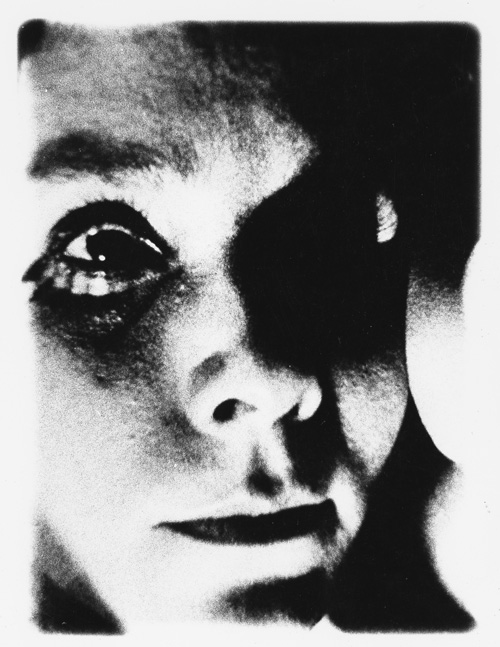

« Ce film, qui fut tourné durant une séance unique de huit heures, met en œuvre, et de manière extrêmement violente, une sorte de passation de pouvoir entre filmeur et spectateur. Sur l’écran, une femme se donne littéralement aux regards. Jusque-là, ces images ne seraient que de tristes images pornographiques softs. Ce qui change tout, c’est que Dowskin « répond » à ce regard en affirmant qu’il lui est bien destiné : recadrages, zoom avant et arrière, plans rapprochés ou plus larges. Nous ne pouvons assumer la place de destinataire, accepter l’invitation, y répondre. Sensation troublante de ne pas être à notre place, d’avoir pris la place d’un autre, de regarder par-dessus son épaule. » (Aline Horisberger)

« This film which was shot during a single eight hour screening establishes, and in an extremely violent way, a kind of passage of power between the filmmaker and the spectator. On the screen, a woman literally gives herself up to our eyes. Up to this point, these images would only be sad variety of soft porn. What changes everything is that Dwoskin “replies” to this way of looking stating that the image is addressed only to him: reframing, zooming forward and back, close ups or wider shots. We cannot comfortably assume the position of the addressed, accept the invitation, answer to it. The troubling sensation of not being in our place, of having taken the place of another, of looking over his shoulder. » (Aline Horisberger)

THE SUN AND THE MOON (2007, 60 minutes, mini-DV/couleur)

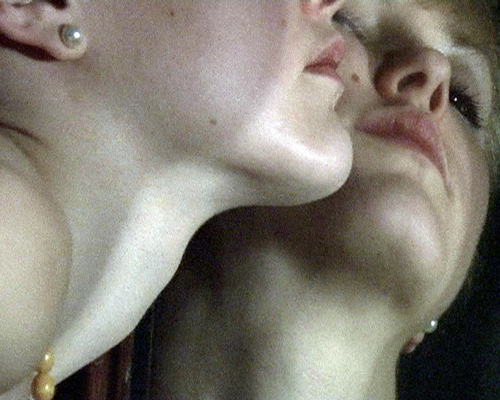

The Sun and the Moon, conte de fée cinématographique, raconte la rencontre terrifiante de deux femmes avec « l’altérité » qui prend la forme d’un homme, abject et monstrueux. Elles doivent soit témoigner, soit accepter et participer à son annihilation. Tous sont prisonniers de leur propre isolement et ont peur de la menace qui doit être affrontée.

Ce film, interprétation personnelle de La Belle et la Bête, concentre préoccupations, croyances et désirs au sein d’images séduisantes qui ouvrent la possibilité de faire entendre de rudes vérités.

The Sun and the Moon, a film fairy tale, is of two women’s terrifying encounter with « Otherness » in the form of a man, abject and monstrous, and for them to either to witness, accept or partake in his annihilation. All are caught in their own isolation and are fearful of the menace that has to be met.

The film, as a personal interpretation of « Beauty and the Beast », enciphers concerns, beliefs and desires in seductive images that are themselves a form of camouflage, making it possible to utter harsh truths.

Repères biographiques

English below

Stephen Dwoskin (1939-2012) est né à New York. Son grand-père russe était danseur et voulait que Stephen le devienne également, mais à l’âge de neuf ans il est atteint de la poliomyélite. Ses déplacements deviennent difficiles et requièrent dès lors une aide appareillée. A l’hôpital, il commence à peindre pour illustrer des livres. En sortant, il débute la photographie et une fois l’école terminée, il étudie le design et la peinture. Le cinéma viendra plus tard, en 1961, lorsque Stephen Dwoskin filmera les pieds de sa femme et réalisera son premier film, Asleep.

L’immobilité physique du cinéaste va donner forme à son cinéma. Dorénavant, à l’aide de la caméra, il va explorer l’espace qui l’entoure et se déplacer avec les yeux. Ce qu’il fait avec une détermination et un désir de vie certains, faisant de ses limitations physiques des outils de réflexion et de fabrication artistique, tout comme les dispositifs de prise de vue et de montage cinématographiques, mis à l’épreuve pour les tirer vers la plus grande expressivité.

Le vent de liberté qui se mit à souffler à New York dans les années 60, une grande période de protestation et d’expérimentation sociale, politique et artistique, a été un vrai déclencheur pour lui. Il a très tôt pris fait et cause pour un cinéma différent, non-industriel, à l’instar du sien et de celui de nombreux autres artistes. Après son arrivée à Londres en 1964, il a participé à la création de la première coopérative de cinéastes en Europe. Dans son livre Film is, publié dix ans plus tard, il rend hommage à tout ce cinéma novateur, qu’il appelle le cinéma international libre.

Stephen Dwoskin n’est jamais rentré vivre aux États-Unis. C’est en Europe que ses films ont connu leur premier succès public, lors du festival international de film expérimental de Knokke-Le-Zout en 1967-68, où il a gagné un prix. Par la suite, plusieurs de ses films ont été co-produits par des chaînes de télévision culturelles dans différents pays européens (la ZDF en Allemagne, Channel 4 en Grande Bretagne, La Sept/Arte en France et en Allemagne). La reconnaissance qu’il a reçue de ses pairs se reflète dans les rétrospectives dont il fait l’objet : Digne (1980), Genève (1981), Festival de film documentaire de Marseille en 1995, Bilbao (1996); Paris/Pantin (2004); Rotterdam (2006); British Film Institute à Londres en 2009, Cinémathèque de Berlin en 2010. Son dernier film date de l’été 2012. Il venait de le terminer quand il est décédé. La première mondiale a eu lieu au Festival de Locarno en août 2012.

Depuis notre passage à Londres, nous avions gardé le contact avec lui. C’est avec grande tristesse que nous avons appris sa mort, en juin 2012.

Une biographie détaillée sur le site www.stephendwoskin.com/02bio.html

———————–

Stephen Dwoskin was born in New York. His Russian grandfather was a dancer, and would have liked Stephen to become one too. At the age of nine however, Stephen Dwoskin contracted polio. He now needed mechanical appliances in order to move about. While in hospital, he began to paint book illustrations. On his release, he took up photography and after finishing school went on to study graphic design and painting. Cinema came later, in 1961, when he shot his wife’s feet for his first film, entitled Asleep.

The wind of change that swept through New York in the 1960s, a period of intense social, artistic and political protest, had a decisive influence on Stephen Dwoskin. He quickly adopted the cause of an other, non-industrial cinema, which included his own films and those of very many other artists. After he came to London in 1964, he co-founded Europe’s first film-maker’s cooperative. In his book Film is, published ten years later, he celebrates all the ground-breaking innovation of the time, giving it the name of International Free Cinema.

His physical immobility has largely contributed to the form his cinema has taken. Using the camera, he explores the space around him, moving with his eyes. And does so with great determination and lust for life. Physical limitations have become an integral part of his artistic reflection and practice, as have the processes of image taking and editing, which he pushes to their expressive extremes.

Stephen Dwoskin never went back to live in the United States. His first public success as a film-maker was at the Knokke-le-Zoute International Experimental Film Festival in 1967-1968, where he won a prize. A number of his subsequent films were produced by cultural television stations in various European countries (ZDF in Germany, Channel 4 in Britain, La Sept/Arte in France and Germany). He has received several tributes for his work, reflected in the following list of film retrospectives: Digne (1980); Geneva (1981); Documentary Film Festival in Marseille in 1995; Bilbao (1996); Côté Court Festival in Paris/Pantin (2004); International Film Festival Rotterdam (2006); British Film Institute in London 2009; German Kinemathek/Arsenal in Berlin in 2010. His last film was completed in the summer of 2012. The world première was during the Locarno film festival in August of the same year, just after he had died.

We had kept in touch with Steve ever since our first visit. We were deeply saddened by the news of his death in June 2012.